- Home

- Maureen Stanton

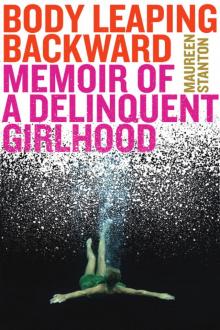

Body Leaping Backward

Body Leaping Backward Read online

Contents

* * *

Title Page

Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Photos

Prologue

Here We Are Living

Tilt

Operation Pocketbook

Conti la Monty

Clarity and Logic

Hello World

Work-Study

Speech Acts

Stop the Dust

Body Leaping Backward

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

Sources

Appendix

About the Author

Connect with HMH

Footnotes

Copyright © 2019 by Maureen Stanton

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected] or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stanton, Maureen, author.

Title: Body leaping backward : memoir of a delinquent girlhood / Maureen Stanton.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018033154 (print) | LCCN 2018052035 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328900364 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328900234 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: Stanton, Maureen, author. | Female juvenile delinquents—Massachusetts—Walpole—Biography. | Drug abuse and crime—Massachusetts—Walpole. | Walpole (Mass.)—Social conditions. |

BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Women. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Cultural Heritage. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Criminology.

Classification: LCC HV6046 (ebook) | LCC HV6046 .S73 2019 (print) | DDC 364.36092 [B]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018033154

Cover design: Michaela Sullivan

Cover photograph © Jaime Monfort / Getty Images

Author photograph © Heather Perry

v1.0619

Lines from “Sodomy” (from Hair): Lyrics by James Rado and Gerome Ragni. Music by Galt MacDermot. Copyright © 1966, 1967, 1968, 1970 (copyrights renewed) by James Rado, Gerome Ragni, Galt MacDermot, Nat Shapiro and EMI U Catalog, Inc. All rights administered by EMI U Catalog, Inc. (publishing) and Alfred Music Publishing (print). All rights reserved. Used by permission of Alfred Publishing, LLC. Lines from “Don’t Let It Bring You Down” and “Only Love Can Break Your Heart”: Words and music by Neil Young. Copyright © 1970 by Broken Arrow Music Corporation. Copyright renewed. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC. Lines from “It’s All Behind You”: Words and music by Andy Pratt. Copyright © 1973 by EMI April Music Inc. Copyright renewed. All rights administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, 424 Church Street, Suite 1200, Nashville, TN 37219. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC.

Photographs used by permission of the author.

For my mother

The first eighteen years really shape you forever. It’s like a glass of water filled with mud. You can pour clear water in until it appears clear, but there’s still mud there.

—Bruce Springsteen

Top, from left: Patrick, Susan, my mother holding Michael, Joanne, my father holding Barbie, Sally, and me, 1970. Bottom left: My mother graduating from nursing school, 1975. Bottom right: Me at fifteen years old.

Top left: Me, Barbie, Sally, and Joanne in Stanton, California, 1976. Top right: Michael, Sally, my father, Barbie, Joanne, Patrick, and Sue, with me patched at right. Bottom left: Me at my work-study job, 1977. Bottom right: Me at Muir Woods, California, 1978.

Prologue

You Can’t Even Get Out

If you grow up on the seacoast, you learn to swim, to navigate choppy water. The flatlands of the Midwest teach you about spaciousness and its possibilities, the safety of sameness but also tedium. In a factory town you learn about labor and time clocks. Growing up in Walpole, Massachusetts, home to the state’s maximum-security prison, I learned about good and bad, about being inside or outside, about escape.

In the mid-1960s, when my siblings and I were little (six of us at the time), if my mother was driving past Walpole State Prison, she would slow the station wagon to a crawl along the shoulder of the two-lane road. “See that place?” she’d say, her head lowered to peer out the window, our faces pressed to the glass. “If you misbehave, you’ll end up in there.” My mother couldn’t put too fine a point on her lesson. “See the fence? It goes all the way around.”

It was strange—that huge building with massive white walls surrounded by dense cedar forest, like something out of a fairy tale. I thought the walls looked like the papier-mâché we made in first-grade art class—that same eggshell color. Around the perimeter was a chain-link fence topped with a curl of razor wire, like our Slinky toy stretched on its side. “If you’re not good, that’s where you’ll end up,” my mother would say. “You can’t even get out. Take a good look. Imagine spending your whole life in there.”

Who knows where we were going on those drives—maybe to the discount clothing store in nearby Plainville. Whatever our destination, it wasn’t urgent enough to prevent my mother from taking advantage of the prison as a behavior-modification tool, a gigantic real-life object lesson. For my mother, the prison was a boon to parenting, an inescapable specter of destiny writ large in black and white, like the stripes of the jailbird in Monopoly. Once we saw the prison, once it lived in our imaginations, my mother could conjure its symbolism to discipline us. If my sisters and brother and I bickered, if we kicked and punched each other or aggravated each other by mere proximity, crammed in the backseat of the car (“Mom, Sally’s breathing on me,” or “Mom, Joanne won’t stop staring at me”), my mother yanked the car to the side of the road or craned her neck toward the backseat. “If you don’t behave, I’ll put you in Walpole Prison!”

A decade later, my mother stands in our kitchen about to drive to the Registry of Motor Vehicles. She is dressed in nice pants and a blouse, her dark brown hair pinned in a twist, mascara highlighting her nearly black eyes, lipstick outlining her movie-star smile. In her late thirties, she is a little thick in the waist after her seventh child, but still pretty and petite—high heels raise her to five feet tall. She looks like who she is—a thirtysomething suburban housewife, not a person about to commit a felony.

I’m fifteen and at least I look like who I’ve become—a druggie, a delinquent. The hems of my ratty jeans are frayed from dragging on the ground, my faded dungaree jacket is too big, my hair is pulled straight and parted in the middle; the start of a vertical frown line divides my brow, mark of an angry young woman. So much has changed in a decade in my family, in the country. Categories have shifted, boundaries blurred. Who are the good guys? The bad guys? What’s right and wrong anymore? Nothing is as clear and defined as it was in those hopeful early days of the 1960s when my mother drilled into her children a strict moral code, simple lessons made concrete by the concrete walls of the prison. Good and bad, inside and outside, the walls a solid, reliable boundary between the town and the prison that shared a name: Walpole.

My mother slides into the driver’s seat of her car, onto the pillow that allows her to see over the steering wheel. Her pocketbook on the passenger seat holds forged papers to transfer ownership of a stolen camper. “Keep your fingers crossed,” she says as she puts the car in reverse. “I could wind up in jail.” Her words have a similar cautionary tone as when we drove by the prison years before, but the message is the oppo

site, and not abstract. She’s not warning against bad behavior but against getting caught.

1

Here We Are Living

I have a memory that, decades old, still makes my heart ache, a filmstrip that ticks through my mind’s eye like this: Late spring 1965, the morning sunny and warm as my family visits our house-to-be in Walpole, a small town twenty miles south of Boston. A sign in a vacant lot reads PINE TREE ESTATES, with a faded map of plots. Estate is an aspiration, an exaggeration of the modest framed-in houses. We are among the first families here, and we feel like pilgrims, settlers. The builder offers a couple of models—split-level ranches, gambrels—so there is the appearance of diversity, but the pattern repeats unimaginatively until the pavement abruptly ends at pine forest. A sign at the top of the street reads, inauspiciously, DEAD END.

My mother, Clarissa, and father, Patrick, my four sisters—Sue and Sally, who are older than me, Joanne and Barbie, who are younger—and my brother, Patrick, also younger, are here. My mother is twenty-six, my father thirty, and the six of us are seven, six, five, four, two, and one—Barbie, swaddled in my mother’s arms, is why we need a bigger house. (Mikey, the seventh, will be born in five years.) My mother wears a sheath skirt and waist jacket, pumps, her dark hair pulled back, with spit curls like earrings. We’ve gone to church and now have driven over to our house being built.

My father is smiling; I can see the diastema in his front teeth, a gap I’ll inherit and close with braces in another seven years. He wears a suit and tie, like when he leaves for work each morning. I don’t know what my father’s job is, and the next year in first grade when Miss Hanson asks us to draw a picture of our father at work, I grow anxious. In the mid-1960s the nuclear family is largely intact, so it’s safe for Miss Hanson to assume that all kids have fathers at home, that those fathers go to work each day. Nuclear family is a curious term, coined in 1946, the year after our country dropped two nuclear bombs on Japan. Nuclear connotes cohesion—protons and electrons revolving around the nucleus—but also an explosion: something bound together, something torn apart.

In class that day, my page blank, I begin to cry. Miss Hanson kneels by my desk. “Does he work in an office?” I recall a visit to my father’s office, many desks in a large room, swivel chairs, typewriters. “I think he is a secretary,” I tell Miss Hanson, who looks doubtful. “Are you sure?” But I’m certain and I get busy drawing a typewriter, happy that I’ve realized my father is that long, important word. When I bring my picture home, my mother says, “Your father is not a secretary.” The way she says secretary, I know it’s lesser, but I don’t know why. My father brings home stacks of three-by-eight-inch rectangles in heavy manila stock and gives them to us for coloring. These papers have tiny square holes punched through them in no particular order, like windows in an office building. I will be in my twenties before I vaguely understand my father’s work as a systems analyst, when computers were the size of rooms and programmed with punch cards.

In the shell of our house we wander through rooms framed with two-by-fours, passing through walls like spirits. I breathe in a sharp pleasant smell, sawdust and wood, but I won’t know its name until shop class in ninth grade, the astringent scent of pine lumber. After we’ve seen everything, we linger in this outline of a house, trying it on like new winter coats, admiring ourselves, the whole of us, measuring the hope we feel in the air, taking breaths of it. We are expanding to occupy this space. This is the age of expansion: the population, the economy, geopolitics, space. To Americans, everything is big and growing bigger. Our family, too: big and growing bigger. The backyard is covered with tons of rocks—pea gravel for a leach field. That night in my dreams the rocks become M&M candies, an alchemy of the imagination, a dream that signifies sweetness, abundance. Beyond the gravel is a steep hill that in four years Nancy Morris will sled down, and break her collarbone, though for now Nancy Morris is a girl I don’t know living in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and nothing is yet broken.

Twenty or so families lived on our dead-end street, as if on a peninsula; there was only one way in, one way out. The families were young, all but one white, with a baby or two born every year, families at the beginning of their promising lives. The houses were painted in primary colors—red, yellow, blue, green, or sometimes chocolate-brown or white. The driveways were paved. The lawns were trim, yards landscaped with shrubbery. I was glad we had shrubs, which thwarted the kidnappers that my Aunt Barbara promised would carry me away in a huge sack if I didn’t behave, shrubs literally a hedge against intrusion.

We were told to watch out for kidnappers, a word that confused me—someone who nabs kids when they are napping. There was a kidnapper in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, the Child Catcher, who rode around in a truck that hid a jail cell. It was unclear what the kidnapper did with the kids once he nabbed them. In bed at night when I couldn’t sleep, I’d watch the window for a silhouette of the kidnapper, who I imagined looked like Andy Capp, that comic-strip character from the Sunday paper, a snub of cigarette glued to his lip and no eyes, just a nose poking out from his cap. When I studied the shadows through translucent curtains, it was Andy Capp I waited for in fear.

In spring and summer parents chatted in the street at dusk while kids played kickball or dodgeball. At twilight mothers stuck their heads out their front doors and screamed the names of their children, calling them home. A few mothers used whistles to summon their kids: two shrill blows for the Stewarts, three short sharp tones for the Murphys. I wished my mother had a signal for us, even though the whistles seemed horrible, like whistling for a dog. That seemed to happen often when I was a child—I envied or desired something that also horrified me.

After the streetlights sputtered on, the older kids played Flashlight Tag, hide-and-seek in the dark. Home base was called “gools.” I don’t know the origin of the word, but my father used it in his games. Gaol is “jail” in Gaelic, so perhaps gools was something my father heard from his immigrant parents or the many Irish in Dorchester, his Boston neighborhood. To us, gools was home, and was always our front steps. When I was nine, ten, eleven, it seemed I’d never tire of flashlight tag on summer nights, of venturing farther from gools, skulking from tree to tree to stay hidden, and then at a carefully timed moment casting myself into the night and racing to gools, to safety. The chase left me breathless, as if I were running for my life.

At the end of our street the pavement stopped abruptly at a bluff, and from its edge we’d leap ten feet below into the forgiving sand. Beyond the sandpit, in the soft duff beneath towering white pines, my sister Sally and Sherry Stewart and I built forts, though we didn’t build them as my brother did, nailing lumber to trees. Rather we outlined rooms on the pine-needle carpet with sticks and rocks: kitchen, living room, bedrooms, sometimes napping on the cushiony moss beneath the pines and balsam firs, like nymphs, listening to the creaks and groans of branches rubbing in the wind. The woods felt like home to me.

One day I picked a beautiful lady’s slipper that grew in the understory, its blossom like a pink silk purse. I presented this exquisite gift to my mother, but she said never never pick them because they were rare and it was against the law. We would have to pay a $50 fine. Sherry Stewart picked the lady’s slippers anyway; she didn’t care about the law. That was the first time I knew of anyone intentionally breaking a law, and that person was a child.

On one side of us lived the Petersons, who’d moved there after their oldest child, Mark, was killed by a drunk driver. The accident left another son, Brad, with a jagged scar above one eye and a plate in his head, my mother told me. I spent an inordinate amount of time trying to imagine the plate in Brad’s head, envisioning a tiny flowered tea plate like my mother kept in a hutch. Later I heard it was a metal plate and I wondered if it felt cold, like the headache you get from eating ice cream too fast.

Across the street were the Gibsons, Connie and Arthur and their daughter, Peggy, her long uncombed hair in knots, “like rat’s nests,” which her mother, unli

ke mine, did not painfully yank out, which in my mind was clearly a failing. Arthur Gibson wore droopy green Dickies on weekends as he tended plots of vegetables and flower beds, his glasses slipping off his pointy nose as if gravity were getting the better of him. Mrs. Gibson always wore snap-down housedresses and open-toed mule slippers with white ankle socks. The Gibsons’ house was always astonishingly and, it seemed to me, unapologetically messy, Mrs. Gibson in the den every afternoon, the blue flicker of television tuned to soap operas.

The Wagners lived next door, Eugene and Joan, and their children, Judy and Billy. The Wagners’ yard was perfect: no toys lying around like in our yard, no wrappers or deflated balls or balloon scraps, or pieces of wood with protruding nails, my brother Patrick’s construction projects. Only forty feet separated our house from the Wagners’, but their split-level was situated downslope from our house, which enabled us to look down upon their lives, to see everything.

Billy Wagner was four when his family moved next door, but already he was bad. When Billy was punished, he was confined to his house, sometimes with yard privileges. Mostly Billy sat at the boundary between our properties, clearly visible by the Wagners’ manicured lawn and our shaggy dandelion-infested grass, which my father avoided cutting in favor of playing tennis on Saturday mornings.

Property was a word I learned early, particularly in its relationship to trespass. In the woods behind our house, signs read NO TRESPASSING—like in church, those who trespass against us. Our properties were like tiny kingdoms over which we reigned. When neighbor kids squabbled, we yelled, “Get off my property!” One day Doreen Randall—the girl whose father was the drunk in front of Tee-T’s downtown, the girl who lived in the house with asbestos siding that I thought of as a “tarpaper shack” like I’d read about in some book—wandered into the Gibsons’ yard where we were playing on the swing set, her smile exposing rotted teeth. Peggy Gibson said, “Doreen. You are not allowed on our property.” I watched Doreen’s face crumple as she walked away: those skinny, dirty legs and scuffed patent leather shoes that we wore only on Sundays. I felt the heat of shame for remaining silent as I pumped my legs higher. But what could I do? It wasn’t my property.

Body Leaping Backward

Body Leaping Backward