- Home

- Maureen Stanton

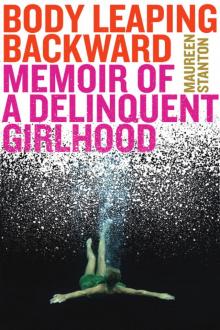

Body Leaping Backward Page 5

Body Leaping Backward Read online

Page 5

Eileen had vast knowledge because her older sister was much older than mine, and because she’d already kissed boys. Eileen the Experienced told us that her sister had hickeys on her breasts. Hickeys were bite marks, Eileen explained. I wondered why someone would do that, or want that done to her. Eileen’s sister shared with her tenets of femininity. “Once you spread your legs for one man, it doesn’t matter how many men you sleep with after that.” It sounded profound.

Everyone had a story to tell except me; I felt naive and sheltered, so I invented a story. I said that Brad Peterson, the boy next door, whom I secretly adored, tied Maureen Murphy, one of the sluts everyone talked about, to a tree and felt her up. I don’t know where this bondage story derived from, and I didn’t make the connection that I’d chosen a slut who shared my name and an older boy on whom I had a crush. Perhaps the bondage relieved “Maureen” of culpability. What could she do? She was tied up, she couldn’t escape and so could not truly be a “slut.” At eleven-about-to-turn twelve, everything was still in my imagination.

2

Tilt

As the 1960s shifted into the 1970s, the decor of our house shifted, too. We knocked down the wall between the kitchen and dining room, crashing a boundary, opening a space. We replaced avocado-green and earth-brown carpets with mauves and cool blues, like the cheap mood rings that everyone wore at school, green dissolving to blue, though after a while the rings turned black and fixed that way, as if to reflect the zeitgeist. In fourth grade, at recess on rainy days my friends and I played 45s, dancing in the back of the classroom to the top hits of 1969.

Take a letter, Maria, address it to my wife,

Say I won’t be coming home, gonna start a new life

And “Leaving on a Jet Plane” by Peter, Paul, and Mary, I don’t know when I’ll be back again. A husband who cheated, a wife who cheated, marriages falling apart, people leaving. I was too young to read the auguries in the lyrics, just the solemn tone of Mary Travers’s refrain, I’m so lonesome I could cry.

Changes, small at first, seeped into my awareness. Off the back porch of our house, a metal garbage can was sunk three feet into the ground, with a step-pedal lid that opened to reveal decomposing slop and wriggling maggots, emptied weekly by an unfortunate man in a golf-cart-like vehicle. Then one year—lo!—trash and garbage were merged and the garbageman became extinct. Then the milkman went the way of the garbageman. No more would anyone find deposited at her doorstep four heavy glass bottles of cold delicious milk sealed with waxy paper caps, set into an insulated aluminum box like an anonymous gift. The garbageman, the milkman—I mark those changes as my first conscious moments of resistance to the future, as if heavy invisible hands on my back were pushing me forward. The future was depicted every Saturday morning on The Jetsons. We would eat dinner as a pill, walk on a conveyor belt to nowhere, the treadmill rolling faster and faster, threatening to suck you under. That treadmill clip made me anxious. You had to keep up; the future was coming fast.

Until sixth grade, girls were not allowed to wear pants to school. At Fisher Elementary we stood outside before the bell rang with reddened legs and numbed thighs, waiting in subfreezing temperatures for the doors to open. Then in sixth grade the no-pants rule vanished mysteriously. I didn’t know that Sue and Sally had taken part in a protest at West Junior High for the right to wear pants, the seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-grade girls refusing to enter the school until the principal came out to negotiate. They struck a deal allowing girls to wear pants on Fridays, but once they’d crossed the pants line, there was no returning. The girls wore pants whenever they wanted.

At first the changes seemed to originate from beyond our dead-end street, like the DDT trucks that cruised slowly past our house, releasing a fog of poison that drifted into our yard, into our neighborhood, settling here in the dead end. Maybe the bad news had always been there, but I’d reached an age when I saw it, noticing things one year that I could never not see anymore. One summer the Gibsons’ lawn turned patchy overnight, it seemed, the way fall arrives not on September twenty-first but on that first morning when blades of grass are sheathed in frost and it’s clearly the end of one season, the beginning of another. The blight seemed mysterious, though it was likely caused by the weedkiller Mr. Gibson sprayed on crabgrass, a scourge that hit suburban lawns like an epidemic. “The weed has become a neighborhood problem, like juvenile delinquency,” Time magazine reported.

Then Mrs. Peterson got breast cancer and neighbors sent their children over bearing casseroles. We all knew that Mrs. Peterson had to wait five years to see if the cancer would return, a ticking time bomb inside her. And then the McKenzies’ new baby died of crib death. Crib death seemed like an omen—its quiet nighttime work, its tiny innocent victim. I asked my mother how the baby died, but she couldn’t explain. A blight, cancer, a death—in my memory these events are clustered like beads on the rosary my grandmother worried with her fingers.

Like a contagion, the bad news entered our house just before I turned twelve, on a spring night when my mother called my siblings and me in from playing kickball for a family meeting. The four oldest girls—Susan, Sally, me, and Joanne—lined up on the couch like starlings on a telephone wire. Patrick and Barbie shared the piano bench. Mikey, just two, was upstairs in his crib. My mother and father sat next to each other on the gold ottoman. “As you know,” my father began, “your mother and I haven’t been getting along.” That’s where my father’s speech ended for me. My mind was puzzling with “as you know.” I’d never seen my parents fight, so I had no clue that anything was amiss. “Not getting along” was visible, tactile, aural—the dull thud of my fist on my sister’s back, board games overturned, Monopoly money fluttering in the air, the names we shouted at each other. Fatso. Pimple-face. Twisty-teeth. Bucky beaver. How could I have missed my parents “not getting along”?

At that moment all the distractions—the shouts of kids playing in the street, the abrasive upholstery of the couch scratching my bare thighs, the bothersome warmth of my sister’s arm brushing mine—faded to background. My eyes fixed on my father’s lip quivering. I couldn’t stop staring; it was so strange, his lip shivering on a warm spring night. My stomach clenched. A tear slipped down my father’s cheek, and then like a chorus we all cried, our last act as an intact family.

After the meeting we were sent upstairs to our rooms, though it was still light outside. When one of the neighbor kids knocked to see if we were coming out to play, my mother said, “No, they are staying in for the night.” In my room I turned over that word: separation. It sounded like something my parents had no choice about, like when I was separated from Martha Wilkins at school for talking during class or passing notes, the teacher moving our seats to opposite sides of the room. This separation felt more ominous, like a rent in the earth, or the planet tilting too far. In fourth grade Mrs. Kannally drummed into our heads the reason we had four seasons, “because the earth is TILT-ed on its axis,” she said over and over, emphasizing her point by tipping the globe she held in her hands. That’s how it felt, the earth tilted and things falling, tilt like in a pinball game when you slammed the machine too hard, tilt and the game was over. Tilt, the family was over.

What was I doing when my father carried his clothes out of the house and never came home again? I have no memory of him walking out with his arms loaded, stuffing things into his car, only that he was gone overnight, which seemed sudden and devious; there had been a plan all along, and they’d only clued us in at the eleventh hour. Maybe if we’d been warned, we might have tried to convince them otherwise, the way I’d tried to persuade my mother not to give away the cardboard-box dollhouse. Were my parents aware that they’d announced my father’s moving out in that bubble of time between May 1, 1972, when President Nixon proclaimed Father’s Day a new holiday, and six weeks later in June when it was celebrated for the first time?

My father didn’t take much when he left: his tall dresser, on top of which was a tray with cufflinks

, his watch with a gold spandex band, the supply of coins replenished each night when he emptied his pockets after work. What I missed most, what seemed starkly absent, were his things in the medicine cabinet in the bathroom: eyedrops and nasal spray for his hay fever, his toothbrush with that weird rubber fin, the minty deodorant, the barbershop-striped can of shaving cream, his razor blades in their little metal container like a suitcase.

Weekend mornings my father faithfully did situps on the floor in his bedroom, wearing a white half-sleeve T-shirt and pajama bottoms. Sometimes I’d sit on his ankles to weigh down his legs as he curled. Afterward I’d sit on the toilet and watch him shave, studying him as he scraped the razor across his throat with quick, sure strokes, the sandpapery sound as he drew the blade along his jawline. “Doesn’t that hurt?” I’d say. “Why don’t you grow a mustache? Did you ever have a beard?” He’d wipe his face with a cloth, missing specks of shaving cream. “You left a spot under your nose.” He’d splash amber liquid from a clear glass bottle into his hands, then pat his cheeks, his skin so pale it seemed translucent, like wax paper, more so in contrast to his coal-black hair. When he left the bathroom to get dressed, I’d run the water in the sink and push the pepper specks of stubble down the drain with my fingers until they were gone. When my father moved out, he forgot his bottle of orange-colored aftershave in the medicine cabinet, and once I unscrewed the round black cap and conjured him.

The separation was an end to intimacy with my father, an end to seeing him in his pajamas day after day, seeing him as ordinary and vulnerable and human—sleepy, crusty-eyed, unkempt, knowing him in all his moods, watching him in his morning rituals, situps, shaving, coffee, the newspaper or Time. I’d hover near him, close enough to smell his coffee-scented breath when I asked for a sip, black and bitter. One of the last images of my father living in our house is this: he is strung up in the doorframe of my parents’ bedroom, rigged to some counterweighted contraption that lifted his head and somehow helped the pinched nerve in his shoulder. He sat in a chair in the threshold of their bedroom, one foot in and one foot out, barely able to move.

My parents’ separation was the first on our street, the first of my friends’ and my siblings’ friends’ parents; we were cultural pioneers in a new landscape. There wasn’t even a television show that depicted divorce until One Day at a Time debuted three years later, in 1975. One afternoon as I walked down our street, Mrs. Peterson called to me. “Maureen, do you want to see my little girl?” When I was in the bedroom staring down at her dough-faced toddler, Mrs. Peterson said, “I don’t see your father’s car in the driveway. Did he move out? Are your mother and father getting a divorce?” I walked fast down the hallway and out of her house.

But we were not alone. My parents’ separation coincided with the beginning of what demographers call “the divorce boom.” Marriage breakups more than doubled over the decade of the 1970s, peaking in 1979 at about 50 percent and hovering there since. In each year of the 1970s, political commentator David Frum wrote, “one million American children lost their families to divorce.” I can see them, fathers with suitcases or garbage bags of clothes, loading up their cars or pickup trucks, backing out of driveways, waving or not; maybe they didn’t want to look back as they slowly pulled away, as my father drove up our dead-end street, an exodus of fathers, the breakup of the nuclear family like a chain reaction. It was nobody’s fault, since there was no-fault divorce, a law passed first in California, effective January 1, 1970, as if opening a gate into a new decade. The bill was signed by Governor Ronald Reagan, who in 1980 would become the first divorced president.

My father moved into a dank apartment on Savin Avenue in Norwood, the next town over, in a neighborhood of closely situated two-story houses turned into apartments. I’d never been in an apartment before; my reference point was that comic strip in the Sunday paper, Apartment 3-G, which I never liked because it wasn’t funny. Why was it a comic strip? My father’s college friend, Dick Walsh, was released from Walpole Prison around the time my father moved out—Dick had been convicted of rape—and a mutual friend asked my father if Dick could stay in the apartment, at least for a while, but my father said no, he couldn’t manage it because he was going through a separation.

Perhaps my father was worried about us staying overnight in his apartment. The four big girls—Sue, Sal, Mo, Jo—slept over there two or three times, but then never again because on weekends we wanted to go to dances at Blackburn Hall or sleep over at our friends’ houses. My parents wanted us to have normal adolescences, I suppose, didn’t want us to resent being stuck home on a Friday night with our father.

What did we do those few nights at my father’s apartment? It seems we had to do something; we couldn’t just be, as we had been at home. Did we play games? Watch television? Instead of our father living with us, he became like a relative, someone to visit, a chore, an obligation. His apartment was depressing, with sparse furnishings, a cheap secondhand kitchen table, mismatched chairs and lamps, a rollaway cot for a couch, a small black-and-white television set on a fold-up tray table. The place emanated loneliness, containing only my father.

For months after my father moved out, he came over every night after work and he’d play the piano before dinner and it seemed like nothing had changed, even though he left at bedtime. At some point, maybe a year into their trial separation, my parents’ marriage counselor told them that my father was coming over too often, that they were not letting go, that my parents must separate. From then on my father had set visiting hours, Wednesday nights, and Friday nights when he picked up Barbie and Patrick and Mikey to sleep over, though eventually it would be just Mikey. That’s when my father began to drift away from me, or I from him.

When my father stood in the kitchen on visiting nights, the burden became to talk, and so the talk became strained. A new formality crept into our relationship, a stiff awkwardness. At first he’d walk into the living room and play the piano as he waited for the younger kids, but as time passed he stopped, as if he needed an invitation into the rest of the house. I could not bear to see my father dumbly standing in the kitchen on Wednesday nights in his slack business suit, tie loosened or undone, his shoulders sunk as if he had no bones, so utterly changed that he was unrecognizable, or on Friday nights when everyone was running around making plans for the evening that didn’t include him.

Often I didn’t come downstairs to say hello. I pretended I wasn’t home, or I left the house before he arrived. If my father tried to hug me, I moved around him like a basketball feint. “I don’t care,” I’d told my friends when my father left, and bragged that now I could get away with stuff.

That June after my father moved out, near the end of sixth grade, I came home from school one day to find huge boxes in our backyard, a pool kit my mother bought with money she borrowed from her mother and by draining all of our bank accounts: the $10 deposits from birthdays, First Communions, Christmases—she literally pooled our savings. For years we’d clamored for a pool. In summers, stuck in traffic on the way home from the beach in the stifling un-air-conditioned station wagon, with seven sandy, salty, cranky kids, the faint low-tide stench of a smuggled horseshoe crab, my mother would say, “We wouldn’t have to go through this if we had a pool.” But my father was reluctant: the danger, the expense.

Maybe my mother wanted to compensate for our father’s leaving by giving us the one thing we wanted most—a pool. Or maybe she thought a pool would distract us from the separation.

Maybe now that she was on her own for the first time in fifteen years she could make her own decisions, do whatever she wanted.

The kit was for a sixteen-by-thirty-five-foot oval-shaped aboveground pool with a six-foot-deep hopper, which the salesman promised would collapse if installed in-ground, as was my mother’s plan. Mr. McGrath, our neighbor across the street who installed pools for a living, warned her, too, but she was undeterred. “Come hell or high water,” she always said. My mother hired an excavator, Leroy Jones,

a barrel-bellied guy who charged just $30 to dig a hole in our side yard. Leroy felt sorry for my mother, who clearly had no money and who was installing a pool with the help of children. All day Leroy scooped earth with his backhoe, chomping a stump of cigar.

Toward the end of the day, Leroy steered his bucket for another bite of earth, but somehow he miscalculated, and before anyone could yell a warning, the backhoe keeled into the hole. Leroy must have felt the weight shift beneath him, because, tubby as he was, he leapt from the driver’s seat before the truck landed on its side in our future pool. Neighbors gathered to watch a tow truck winch the backhoe out of the pit.

Leroy’s excavation wasn’t quite deep enough, so each day we shoveled dirt and added it to a giant mound Leroy left. For days and days we dug and shoveled and pushed wheelbarrows of dirt into our side yard, spreading it evenly over the ground, digging and shoveling and hauling under the broiling sun like members of a chain gang. Sometimes Drew Peterson from next door helped, but the burden of the work was left to a skeleton crew: my mother; me, twelve; Joanne, eleven; Patrick, nine; and Barbie, eight. Mikey was two. Sue was fourteen and had gotten her working papers, basically a permission slip from a parent, and been hired at the brand-new McDonald’s. By dint of birth order as the oldest, or maybe because of her empathic disposition, Sue took care of the rest of us, which included paying for food and pool supplies with her paycheck or bringing home leftovers from McDonald’s.

Sally, at thirteen, was inside making lunch or dinner. Sally had little to work with as we were low on funds, but she had a flair for cooking; she faithfully watched TV shows I thought painfully dull, Julia Child and The Galloping Gourmet. When we played restaurant as little kids, I was the waiter, with a neatly folded dish towel draped over my arm, and Sally, the chef, prepared hors d’oeuvres, peanut butter toast cut into bite-sized pieces topped with a square of Life cereal. For her tenth birthday Sally asked for homemade ravioli for her special meal, she and my mother all day hand-rolling sheets of pasta, filling and cutting, the kitchen a floury mess.

Body Leaping Backward

Body Leaping Backward